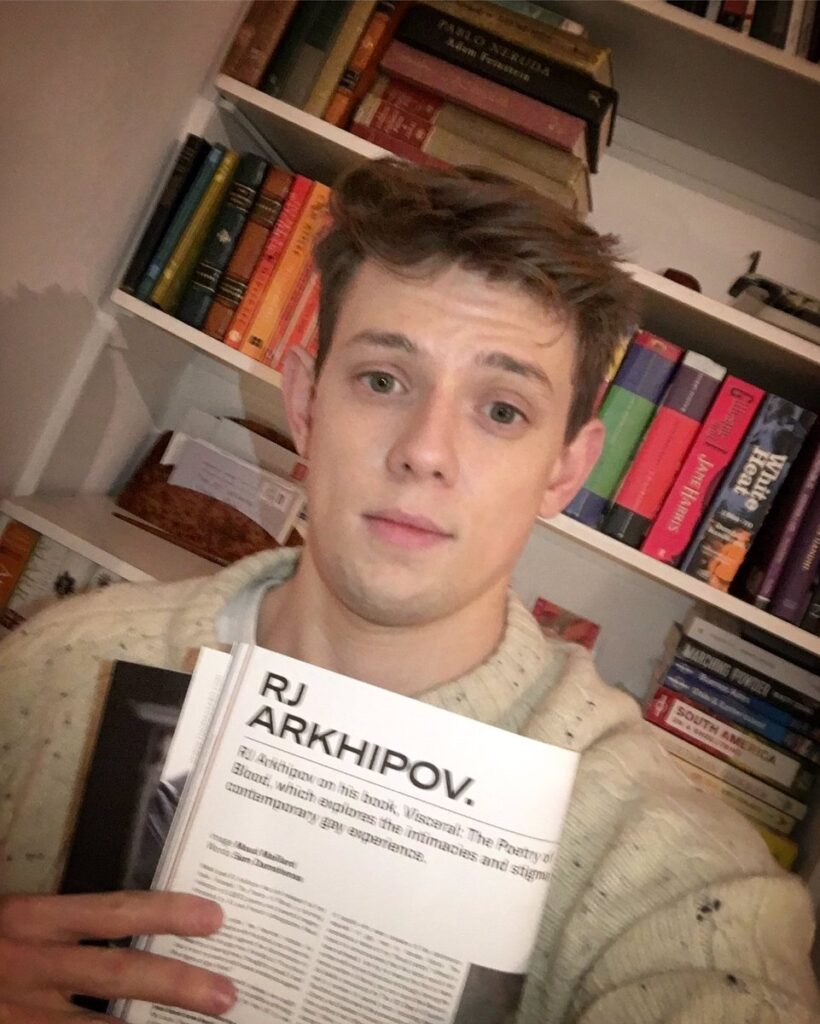

The Welsh poet RJ Arkhipov has earned international recognition because of his ‘blood poems’. One of his many trips made him meet the Argentinian writer Nicolás Colfer, who usually writes for La Revista Diversa. This time, Nicolás plays the part of the interviewer in order to let us know RJ better.

On May 4th, the tandem Arkhipov-Colfer will be presenting a selection of poems at the artistic exhibition ‘Camino a Stonewall’ in Buenos Aires

Tell us about your ‘blood poems’

Blood is a substance of potent metaphor. Notions of family, fertility, violence and stigma are all tied up in it. Blood courses in constant flux throughout our bodies from before we are born to the moment we die, maintained by the devoted beats of our heart.

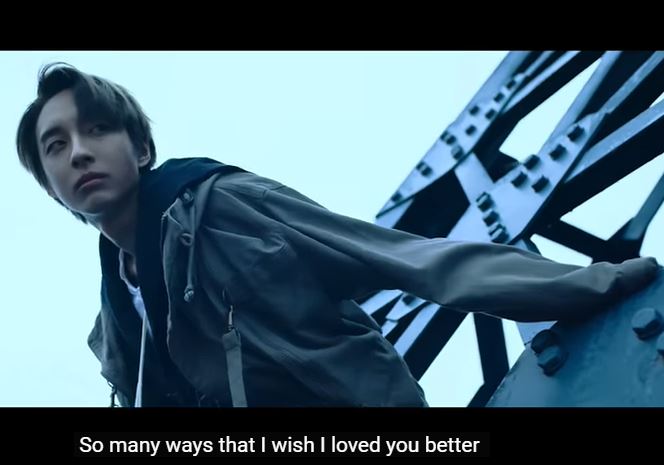

Last year on World Blood Donor Day, I published a collection of poems, essays, and photographs— titled Visceral: The Poetry of Blood—which explore both the polysemic nature of blood, particular through the lens of the gay male body. I began writing the book began back in 2015 with a handful of poems I wrote using my own blood as ink to protest the gay blood donor ban which is still in place in many Western countries, including most of Europe and the United States of America.

In Pablo Neruda’s poem La Palabra, the Chilean poet exclaims “Nació la palabra en la sangre, creció en el cuerpo oscuro, palpitando, y voló con los labios y la boca.” I spent many months pondering this stanza—which adorns the epigraph of Visceral—and believe there is profound truth and essential instruction in these words.

Your bio is usually opened by the fact that you were ‘Born in Wales and reborn in Paris’. Why do you refer to two different births?

This is a very interesting question. One that requires a little context. I was born and raised in Wales and left my country to study in Paris at the age of eighteen.

In Paris, I came to terms with who I truly was, simultaneously realising my calling as a poet and accepting my homosexuality. As is tradition for many poets and writers (including Pablo Neruda, who was given the name Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto when he was born), I changed my name. In many ways I was reborn in the French capital. Paris was my chrysalis. My metamorphosis: poetry and sensuality.

Have you tried making poetry in your non-native languages?

I think poetry, for most poets at least, is a non-native language. You learn it through the medium of your first language. In some ways, it’s the antonym of your native language. You are invited to disregard many of the rules of grammar, punctuation, and syntax. Or perhaps poetry is true language, where you are invited to feel natural flow of words, rather than arrange them by the rules you have learnt by rote.

As for writing in other non-native languages such as French or Spanish, I have written in these languages, but the language of my poetry (for now at least) is English.

That said, I have incorporated words from other languages here and there where there is no perfect translation into English. These words include ‘hiraeth’ in my country’s native language of Welsh; ‘retrouvailles’ in French which I find is not perfectly translated by ‘reunion’; and ‘descuentro’ in Spanish, which has no counterpart in English.

You once told me about your preference for Neruda and how much his work keeps on inspiring you nowadays. Curiously, Neruda’s a straight poet whose idea of love is quite traditional, but you write about gay love. Most importantly: about gay Desire. How do you manage to keep your distance from tradition? Is it possible for LGBT poetry to drink from the fountains of straight poetry?

I think like every member of the LGBTI community, the letter which represents us, while very important to our identity, is not the entirety of our identity. Neruda was full of curiosity, travelled far and wide, and had a profound connection with France and Russia, as do I. The seas and the forests and the stars abounded in his poetry, as they do mine. His poetry, like mine, is both sensual and political.

I’m not sure if the body must be a part of poetry today, but I am profoundly inspired by the body. Especially the male body. I very much imagined my book, Visceral, as a living, breathing, pulsing body when I wrote it. A body through which the poetry of blood courses, and in which each of the chapters are organs.

Your ‘blood poems’ are gathered in a beautiful book, full of pictures of your own body. Traditionally, poets were absent of body, so to speak. No one seemed to care about the flesh behind the words, maybe because poetry was supposed to be always transcending flesh. But here we are: 21st century, the age of the flesh constantly exhibited and yet, maybe, the age of poetry reborn. Must the body be a part of the production and exhibition of poetry nowadays? Why do you think nudity is so important for queer arts and contemporary arts in general?

As for the importance of nudity in queer or contemporary art, I would posit that the male nude has been central to the work of artists—especially sculptors and painters—for thousands of years. Only since the war has the male form seen itself eclipsed by the abstract and the conceptual.

Our community held onto the male nude, for visceral reasons. Poetry in my opinion is at its height when it is felt, not thought. Our feelings are intrinsically bound to our bodies. We should embrace our sensuality.

What do you think is the key to contemporary LGBTI poetry?

Looking back? Struggle. This year, we celebrate fifty years since the Stonewall Riots: the advent of the gay liberation movement. We fought so hard to get where we are today. We cannot be complacent. That said, looking forward, I hope we allow ourselves to be imperfect, to make mistakes, and to diversify within.

Now, a more serious matter: do you prefer them Welsh, French or Latinos?

Conozco la piel de la tierra y sé que no tiene apellido.

Where are you now? When are you coming back to Buenos Aires?

At this very moment, I am in London. I hope to return to Buenos Aires as soon as possible, though I am aware that

I have not long left this beautiful city. Perhaps I shall return in November for Pride. I am especially disappointed to not be able to attend, in the flesh, the El Camino A Stonewall exhibition at Le Gurru this weekend. I am grateful that my poems have travelled so far and, thanks to a certain poet by the name of Nicolás Colfer, ventured into the language of the River Plate.