Deifying Matthew Shepard, Harvey Milk & more

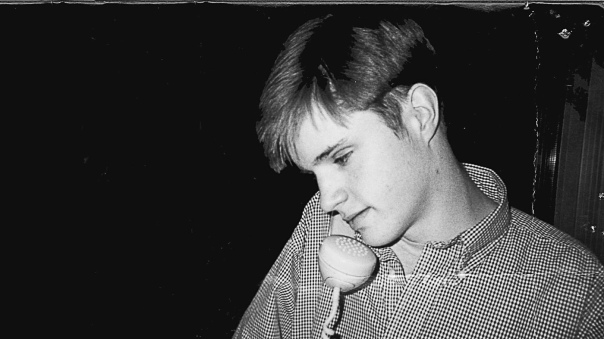

When news broke that Matthew Shepard’s remains were finally buried at the National Cathedral some 20 years after his death, we were reminded of the collective grief the nation felt after the brutal, senseless murder of the waiflike 21-year-old. In the intervening years since he happened into a bar where he met up with two men who lured him into their truck, robbed him, and drove him to a desolate stretch of highway outside Laramie, Wyoming where they pistol-whipped him, tied him to a wooden fence and left him for dead in the cold night air, Shepard had become more than an emblem of the senseless hate crimes perpetrated against the gay community, he had become a martyr.

Shepard’s place among sacrificial victims was solidified when more than 5,000 people gathered on the steps of the Capitol to mourn his death and cemented when Congress passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which broadened existing law to include crimes triggered by sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, race and disability. Byrd was an African American man murdered by three white supremacists in Jasper, Texas. On June 7, 1998, they dragged his body for three miles behind their pickup truck. Although Byrd wasn’t gay, his inhumane murder serves to remind us of the hate that permeates society.

In his book, Dying to Be Normal: Gay Martyrs and the Transformation of Sexual Politics, author Brett Krutszch theorizes that LGBTQ activists are using religion to make the argument that gays are essentially the same as straights and deserve the same equal rights. He points to the veneration of Shepard, Harvey Milk and other high profile gay victims, as well as campaigns like the It Gets Better Project, which he believes promotes the notion that “like Christ’s suffering on the cross, one’s trials today can lead to a better tomorrow.” Krutszch says that national tragedies like Orlando’s Pulse nightclub shooting show how activists use headline-grabbing deaths to gain acceptance, shape the debate over LGBTQ rights and foster assimilation.

Krutszch maintains that Mr. Shepard’s 1998 murder is steeped in religious imagery. Just the thought of the all-American boy-next-door tied to a fence conjures up images of the crucifixion. He concludes that Matthew Shepard’s resulting canonization is due to the interplay of religion, death and LGBTQ politics and that “martyrs as emblems can be changed into more respectable figures than they were in their lifetime.” We may never know if Mr. Shepard was the innocent victim most people believe he was, or as The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths About the Murder of Matthew Shepard indicates, he was a meth dealer who not only knew his killers, but was sexually involved with one and that his death was the result of a drug robbery gone bad.

Whatever the motive for his murder, Shepard has become a shining symbol in the pantheon of almost exclusively white gay martyrs. The group dates back to the 4th century when Sergius and Bacchus, two Roman Christian soldiers who happened to be lovers, took part in a rite called adelphopoiesis (the ancient equivalent of same sex marriage) and refused to attend sacrifices for Zeus, thereby revealing their Christianity. The pair was paraded through what is now Syria. They were dressed in women’s clothing and tortured to death. They lived on through fervent followers and the churches that were dedicated to them throughout The Byzantine Empire.

Any conversation about modern-day martyrs would not be complete without mentioning Harvey Milk. He was the first openly gay elected official in California. Krutszch described Milk as “a secular Jewish, Yiddish-speaking, anti-monogamist” who was transformed by activists who “downplayed his Jewishness, depicted him as committed to fidelity and presented him as someone whose death, like Christ’s crucifixion, transformed the world.” One can argue the validity of that characterization, but it is hard to deny the contributions Milk made as San Francisco’s District 5 Supervisor. Those included defeating Proposition 6 that would have banned lesbian and gay educators from teaching in California public schools, and his efforts to pass legislation that prohibited discrimination in housing and employment based on sexual orientation.

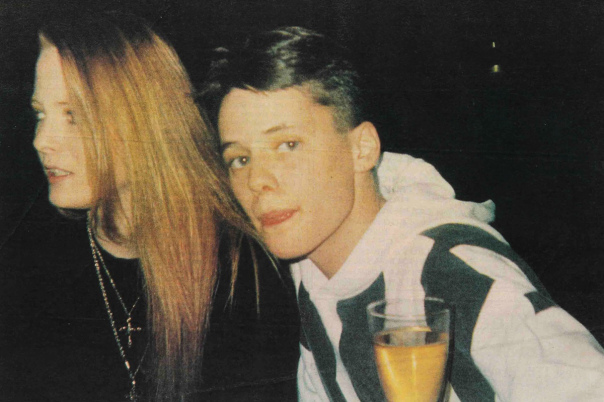

Tyler Clemente may be less well known than Milk and Shepard, but like their deaths, his was another flashpoint. You may remember reading about his suicide in 2010. Clemente was an 18-year-old Rutgers University student who jumped from the George Washington Bridge after his roommate used a webcam to spy on him kissing another man. The video was posted on Twitter.

Most homosexual martyrs are white, but they are not all men. Brandon Teena, born Teena Renae Brandon, became famous when Hilary Swank played him in Boys Don’t Cry. The 21-year-old Teena was living a quiet transgender life in Humboldt, Nebraska, dating 18-year-old Lana Tisdel and hanging out with two ex-convicts John Lotter and Marvin Thomas “Tom” Nissen. Everything was fine until December 19, 1993, when Teena was arrested for forging checks. He used his one phone call to call Tisdel. She got the surprise of her life when she came to bail him out and was directed to the women’s prison where Teena was being held.

At a Christmas Eve party a few weeks later, Lotter and Nissen forced Teena to remove his pants, proving to Tisdale that he was a woman. Later that night, Lotter and Nissen forced Teena into a car, drove him to a deserted area, attacked and gang-raped him. Fearful that Brandon would file a police complaint, the pair murdered him on New Year’s Eve. While his family buried him as a female (his tombstone reads “Teena R. Brandon, Daughter, Sister and Friend”), the death of Brandon Teena is credited with raising awareness of transgender issues in the same way that Matthew Shepard’s became a clarion call for injustices directed toward gay men.

While real-life suffering seems like a necessary prerequisite for martyrdom, some fictional characters like Brokeback Mountain’s Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar have transcended fictional status to take their place in the cultural zeitgeist. Brokeback author, Annie Proulx, said the characters Jack and Ennis were her first two that felt “really damned real” and “got a life of their own.” She also said, “Unfortunately, they got a life of their own for too many other people, too … the audience that Brokeback reached most strongly have powerful fantasy lives. They can’t bear the way it ends. So they invent all kinds of boyfriends and new lovers and so forth after Jack is killed. They can’t understand that the story isn’t about Jack and Ennis, it’s about homophobia.”

Gay martyrs like Matthew Shepard, Harvey Milk, Brandon Teena and even Brokeback’s fictional characters are often a byproduct of homophobia, when people who find themselves outside the mainstream and are struggling to just be who they are.